Remarks of NMC Board Chair Charles J. Sanders on World IP Day to the US House of Representatives, Washington, DC.

April 29, 2025: The Awesome Soft-Power of American Music

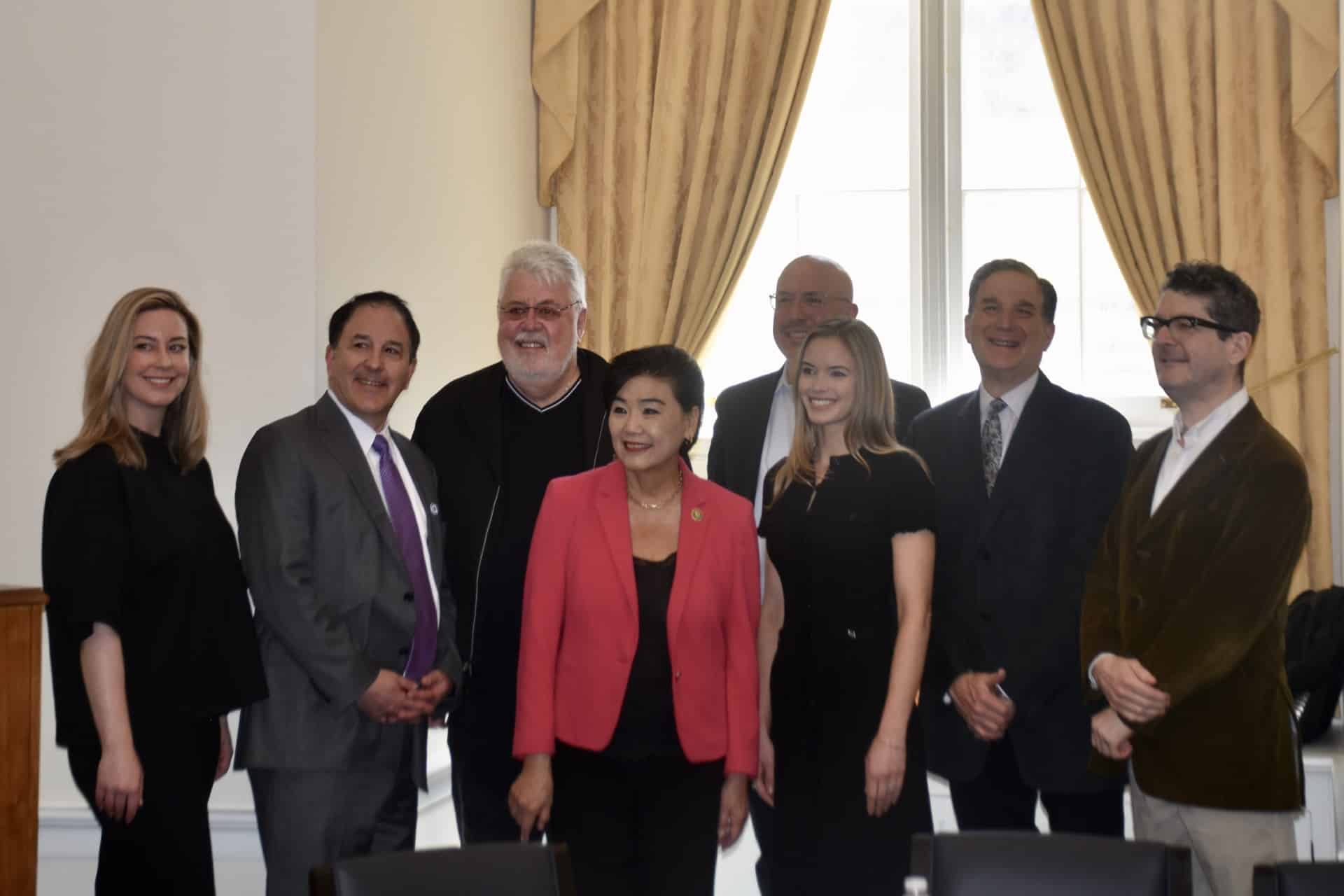

NMC Chair Charlie Sanders (representing SGA), Todd Dupler of the Recording Academy and Ashley Irwin of SCL helped lead the 2025 World I.T. Day observances on Capitol Hill organized by the US Copyright Alliance in conjunction with the US House of Representatives. The April 29th program also included welcoming speeches by Reps Judy Chu (D-CA) and Ben Cline (R-VA), who were among the many interested Congressional members and staffers to attend.

The message championed by the NMC attendees was the importance of protecting the enormous cultural and commercial benefits garnered by the United States through its music community. Sanders’ comments, included below, are representative of the view that the “soft power” of American music is one of the greatest assets the United States has in regard to international diplomacy, and must be safeguarded to the greatest extent possible.

For more than three decades, it’s been my privilege as an adjunct professor of law and music history at New York University to help students gain a sense of pride for the incredible catalog of works that comprise the American musical repertoire. I’m pleased to report that even after all this time, doing so still requires only to underscore the obvious.

Over the past century and a half, American composers, songwriters and recording artists have not just led the world in musical creativity. They have utterly dominated that space during a golden era of 20th century excellence, and continue to do so today. A recent recording industry study of global music distribution found that American songs and recordings continue to comprise a huge percentage of the music charts throughout the world, often constituting upward of an astonishing 90% of the top numerical positions.

There’s more. Solely in terms of hard numbers, the US music industry contributes well over an enormous $200 billion annually to the American economy (GDP), supporting some 2.5 million jobs and over 250,000 music venues and establishments. But even those eye-opening statistics tell only part of the story behind the economic and cultural engine that is American music.

This level of sustained cultural and commercial achievement cannot rationally be attributable to mere chance. Rather, it stands as a living tribute to the unique quality of America’s creative melting-pot. Starting in New Orleans during the 1800s with the synthesis of musical influences from around the world into jazz, gospel and blues, the US music creator community –supported by legal protections and economic incentives provided by Congress– has succeeded in fostering the advancement of the musical arts in America to the very highest levels of human achievement and commercial success.

The benefits of this phenomenon, however, go far deeper than the billions of dollars in US GDP they produce. By consistently creating the music the world loves, the United States has realized political, social and economic value far beyond the balance of trade benefits music sustains. It has, in fact, helped produce the rarest of all geo-political commodities: lasting good will.

To fully appreciate the value to the United Sates of that intangible, good will element — and the need to continue to nurture and protect it– it’s crucial to understand the nature of music itself as the most uniquely passionate and persuasive artistic discipline. Those characteristics have a great deal to do with the extraordinary influence and soft power music produces throughout the world, often to America’s enormous benefit.

As the iconic American photographic artist and amateur pianist Ansel Adams explained it, music is undeniably the most expressive of the arts, surpassing even photography in its ability to convey a message of deep emotion with immediacy. Music’s almost magical ability to inspire genuine and enduring human feeling, whether spiritually or intellectually based, simply makes it more affecting than any other art form. Grasping that distinction makes it easier to understand the extraordinary influence of music creation on American culture, and of American music on the world.

When singer/songwriter Billy Joel was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame a number of years ago, he spoke of an epiphany he had concerning what American music has meant to the world. Performing the very first foreign rock concert in Moscow following the initial relaxation of the Soviet Union’s “iron curtain” policies in 1987, Joel spoke of being terrified that those who showed up to see him would know nothing about either his music or the American rock and pop tradition.

His shock at hearing Russian fans cheering wildly and phonetically singing his lyrics back to him in English, as well as the lyrics of Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, Carole King and other legendary American songwriters, opened his eyes to the reality that music had been a Cold War bridge between America and the rest of the world all along. He was both thrilled and moved, he said, realizing the role music has played in humanizing relations even among people who had been taught to view one another with grave suspicion.

American folk music giant Pete Seeger had the same experience in Barcelona after the fall of the Franco regime, as did US rocker Steven van Zandt in Johannesburg following the end of apartheid. The crowds joyfully sang the lyrics of freedom right back to them.

In short, the affection for American music around the world as an emblem of free expression and democracy had made it one of our nation’s most important exports, a non-partisan gift to the world that redounds to our global benefit every single day across every economic, political and social sector.

The blessings that American music has brought to the citizens of our own country, however, are of an even greater magnitude. Throughout our history, not a single, popular social movement, not a single time of tragedy to be overcome, and not a single defense of freedom in war, has been conducted without the crucial influence and soft power of music being brought to bear for the greater good.

None other than the quartet of Abraham Lincoln, Henry Ward Beecher, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Beecher Stowe utilized the magnificent Anglo-American hymn “Amazing Grace” to champion an end to slavery in the days leading up to the Civil War. Stowe even inserted the lyrics into her landmark abolitionist novel, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

One hundred years later, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. began the most eloquent speech of his life by extolling the virtues and strength of the song “We Shall Overcome” and its incalculable contribution to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s.

In 1932, the country was calmed and inspired by lyricist Yip Harburg’s awesome message of proud hope amidst the crushing despair of the Great Depression in his song “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” The nation grew more empathetic, according to then-presidential candidate Franklin Roosevelt, as a result.

The examples are legion. But I want to close with one more story involving Yip Harburg that perhaps illustrates the awesome power of American music more forcefully than any other.

It was 1938 when Harburg and his writing partner Harold Arlen sat down and composed what is generally revered as the world’s most beloved popular song, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” Most of the song’s millions of devotees cite the hope they perceive as being infused into Yip’s lyrics as the source of the song’s enormous appeal (in addition to its extraordinary melody). In reality, however, the American composers viewed the song as more of a scream of anguish for a world about to descend into genocidal catastrophe, and a prayer for peace that they knew would likely go unanswered.

But those fears and doubts WERE answered, by two other American songwriters named Nat Burton and Walter Kent. They well understood the dark foreboding contained in Harburg’s closing lines sung so poignantly by Judy Garland: “If happy little bluebirds fly beyond the rainbow, why, o why can’t I?”

And so as London was subjected to sixty consecutive days of blitz bombing by the Nazis in an attempt to break the spirit of the British people, and as the nightmare of world war turned into savage reality, Burton and Kent replied to Harburg and Arlen with a new song of their own. “There’ll be bluebirds over, the white cliffs of Dover,” they wrote reassuringly, “tomorrow, just you wait and see. There’ll be love and laughter, and peace ever after, tomorrow when the world is free.”

The heroic English singing star Vera Lynn recorded it, and those two songs became the musical backbone of the morale-lifting spirit that both FDR and Winston Churchill had asked and prayed for in support of the War effort. (A third was “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane. Take a close listen to the original “we’ll have to muddle through somehow” lyrics of that masterpiece the next time you hear it, and you’ll see what I mean).

That is the soft power of music, comforting, inspiring and lending courage to millions of people in their struggle to rekindle peace and freedom in a world gone mad. The music succeeds, even under the most fraught circumstances of the past two thousand years.

Music creation is among America’s greatest joys, its most lucrative and powerful endeavors, and its most dominant and influential exports. Our goal here today is to point this out in compelling ways, and to ask for Congress’ continuing support through laws that protect the art and commerce of music. We are proud of what we do, we are proud as Americans, and we ask you to join us in turning that pride into positive protections for American music creators.

The effort, we promise, is well worth the return.

Charles J. Sanders is chair of the National Music Council of the United States and Outside Counsel to the Songwriters Guild of America.