Ongoing Attempts to Ban The Song “Glory to Hong Kong” Illustrate Just How Powerful –And “Dangerous”– Music Is Perceived to Be

We’ve all seen the recent headlines from around the world. Musicians, songwriters, and composers attacked as rabble-rousers and enemies of the state. Singers arrested, their performances banned as un-patriotic or sacrilegious. We’ve even seen lethal attacks committed against music creators for refusing to perform. And just a few months ago, we saw legal action instituted by a foreign global power against the performance of domestic protest music on a global basis.

No matter our individual political or musical affiliations, the mission of the American music community is clear. We must quickly and effectively formulate ways to help curb this international trend of governments singling out artists and music creators for global punishment, due in large measure to fears over the inherent political power of music.

By way of example, one recent instance illustrating this distressing pattern is currently playing out in Hong Kong. There, amid civil unrest in 2019 over Chinese Government efforts to crack down on what it deems as speech dangerous to national security, a pro-independence leader known only by the pseudonym “Thomas dgx yhl” penned a song known as “Glory to Hong Kong.”

The composition was immediately embraced by Hong Kong rights protesters, translated into various languages, and eventually widely recorded and electronically distributed. Before long, those recordings were being played not only on the Internet, but in Hong Kong shopping malls and at sporting events and other gatherings, prompting public sing-alongs that have increasingly alarmed Chinese Government officials in both Hong Kong and Beijing.[1]

A little over six months ago, the Beijing-aligned Government of Hong Kong announced it had heard enough. Having previously banned the secessionist anthem “Liberate Hong Kong” after protests began in 2019, the Government went to court last June 2023, seeking an even broader injunction against “Glory to Hong Kong.” That motion, if granted, would have barred performance, broadcast, and distribution of the song throughout China, potentially leading to the punishment of Chinese citizens –and companies merely operating in China– for violating the ban anywhere in the world). According to the Government’s court submissions, the song’s lyrics are meant to provoke secessionist acts in violation of Chinese law, and the court should act to eliminate the dangerous confusion that has been caused by the “mistaken use” of the song in place of the official Chinese National Anthem at over 800 Hong Kong and international events so far.[2]

As is often the case when governments attempt to ban musical works, the song instantly skyrocketed in popularity in China and around the world. Within days of the court filing, “Glory to Hong Kong” topped the Apple iTunes charts. That development, however, may have resulted in further action by the embarrassed Governments of Hong Kong and China. The original version of the song recorded by DGX Music (presumably related to Thomas dgx yhl) was suddenly pulled (at least temporarily) from global music streaming platforms such as Spotify, Apple Music, Facebook and Instagram’s Reels system.

Obviously, what we are witnessing in real time is another in a nearly endless series of attempts by governments and powerful interests around the world –representing all political persuasions– to forcibly remove politically contentious musical works from the public sphere and punish their creators and performers.

This past March 2023, NMC, in conjunction with the Paris-based International Music Council (IMC), explored the historical roots of this phenomenon in the hopes of helping the world-wide music community to fashion strategies for ensuring more effective, speech-related protections for music creators in the future. NMC’s extensive briefing papers for the symposium trace the long litany of repression and coercion against individual creators who used their music to protest social and political injustice, including the 1973 murder in Chile of folksinger Victor Jara by the extreme right-wing Pinochet regime, the genocide carried out against Cambodian musicians and composers by the extreme left-wing Khmer Rouge Regime in the mid-late 1970s, and the attempted erasure of Native American/First Nation/Aboriginal music and culture by Constitutional democracies including the United States, Canada, the UK and Australia—efforts that over the course of centuries often resulted in the brutal deaths of those who resisted.[3]

Music-based repression and coercion, NMC concluded, are clearly global problems unlimited by either their political or geographic origins:

Music’s dual, facile ability to serve as both a powerful tool of propaganda and as an existential threat to power structures and political leaders has made it a prime focus of nervous governmental concern over the entire span of history….Music creators and performers have not only been frequently subject to pressure to conform and participate in governmental propaganda efforts, but also to repressive actions up to and including murder to enforce the silence of those dangerous, high-profile individuals who will not comply. In many cases, this effectively neuters the most persuasive voices of protest, while at the same time setting an example of what happens to those less visible citizens who choose dissent. The repression of music and creators is a government’s way of warning all of its people, “if this is what we’ll do to them, imagine what we’ll do to you.”

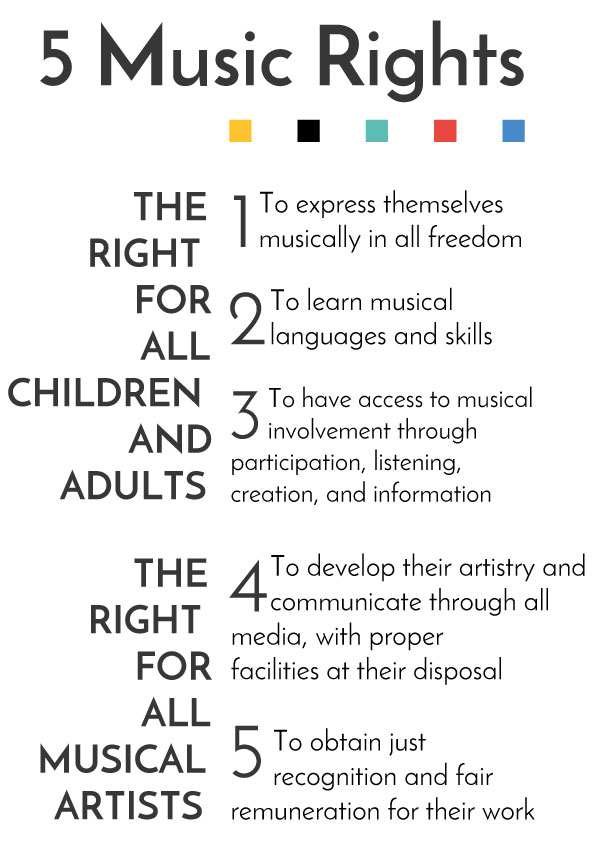

For the American music creator community, initially it’s that last point that must be our paramount concern. While we may argue over whether certain musical expressions (other than outright hate speech) constitute patriotism or treason, it is incumbent upon us to champion the position that violence and imprisonment for peacefully expressing unpopular views should not be imposed on any person by any government, anywhere. Though speech freedom advocates may argue for broader efforts to protect free musical expression –and in the future that may come– job one is to protect the lives and liberties of music creators who have been singled out today for political punishment.

How can we accomplish that duty? At the NMC symposium, international experts and activists such as Ole Reitof of UNESCO, Julie Trébault of the Artists at Risk Coalition, Mark Ludwig of the Terezin Music Foundation, Dr. Ahmad Sarmast of the Afghanistan National Institute of Music, and Arn Chorn Pond of the Cambodian Living Arts organization, all agreed on the opportunities for the US music community to protect fellow, global music creators and performers from official repression by speaking out in appropriate ways. Their advice may be distilled to three basic principles:

First, do no harm. This Hippocratic starting point for every effort to assist requires that all international actions must be carefully calibrated to avoid backlash against the endangered individual or group, and should be undertaken only in consultation with those knowledgeable about the local intricacies related to each incident.

Second, take action by shining a spotlight in the United States on the most egregious cases of music suppression wherever in the world they take place. Write letters to the White House, to Congress, and to the US State Department and the US Trade Representative concerning individual cases, requesting that the US Government take appropriate steps to save the lives and freedoms of those at risk. (Other actions may be contemplated, but only after the “no harm” principle has been fully strategized).

Third, for those not willing or unable to take such actions, lend support to organizations engaged directly in protecting the lives and liberties of members of the music community around the world.[4]

Artistic activism and the defense of it will never be an act of courage devoid of risk. The ability in the US to speak out on such issues principally without fear of government reprisal, however, places on us a special responsibility to shine that brighter light on these escalating injustices and attacks. Our community’s responsibilities are to ensure that such anti-democratic activities not remain hidden in the shadows, no matter where in the world they occur—including within our own borders.

If history has taught us one thing about the persecution of artists and creators, it is that silence is neither an effective nor an acceptable strategy for putting an end to it.

Charles J. Sanders

Chair

The National Music Council of the United States

[1] An English language version of the song is accessible at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6yjLlYNFKCg.

[2] Hong Kong, a former British protectorate the rule over which was transferred to Beijing in 1997, has continued to maintain its own political and economic systems for the past quarter-century. Within the past decade, however, the Government of China has concentrated its efforts on bringing Hong Kong more closely in line with Beijing’s governing philosophies—including the stricter control of political speech. In its submission to the court, the Government pre-emptively sought to quash accusations of censorship by asserting that Beijing “respects and values the rights and freedoms protected by the Basic Law (including freedom of speech), but freedom of speech is not absolute…. The application pursues the legitimate aim of safeguarding national security and is necessary, reasonable, legitimate, and consistent with the Bill of Rights….”

[3] See, https://www.musiccouncil.org/music-politics-history/. The author of this statement was also the author of the Briefing Papers on behalf of the NMC.

[4] For a list of some non-profit organizations engaged in such activities, see, https://www.musiccouncil.org/protecting-free-speech-in-the-global-music-landscape/